Today each country has its own mechanisms to fight illegal migration, but some have demonstrated not having any limits in the way this should be done, no matter if they are children or adults. The Australian government has made children criminals for traveling without permits making offshore imprisonment on islands, just as was done decades ago in the West for the worst, more dangerous criminals.

Unprecedented Australian detention tactics violate child rights

The history of detention in centres in Australia is peculiar, as it is known for being one of the most strict borders and immigration controls in the world. The adoption of child detention as a strategy was instigated with the objective to handle and stop the arrival of migrants in Australia.

Because of the willingness to completely stop illegal migration, the Australian government put in place offshore detention centres. This led to an extreme situation where an almost unique system of indefinite detention was implemented, leaving detained parents and children in complete uncertainty for years, not knowing what their future would be.

Children coming to Australia by boat face the greatest danger. Indeed, the border violence exacted against illegal migrants is widely acknowledged. Some children travel with their parents, but others – teenagers and young adults – travel alone. The majority of detained minors are located on Christmas Island, Nauru Island and Manus Island. Some boats are also taken back by the Australian military to their country of departure.

Unaccompanied child, Christmas Island

Living here is hard. The tension in here and the tension from home. Too much sad[ness] … whenever I call home they ask when I will be released. I tell them Inshalla (God willing) … Many people here are hurting themselves. Boys cutting hands, arms … I was thinking about that.

(Australia HRC, 2014)

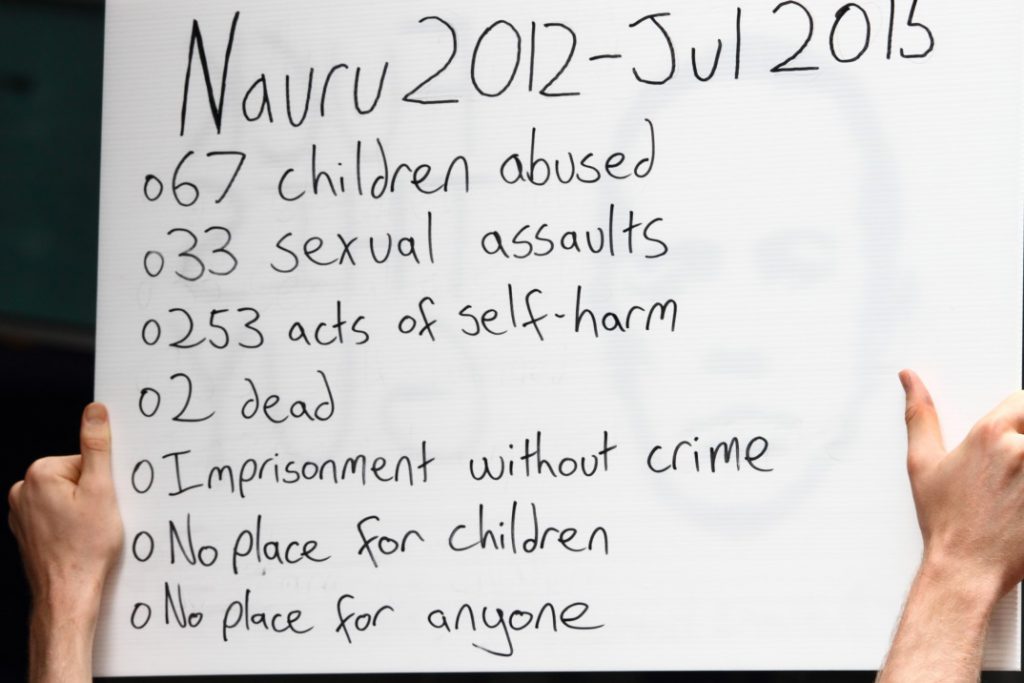

In 2018, 119 children were still detained in Nauru (CNN, 2018), where a seriously ill 12-year-old boy had to be transferred to the Australian mainland after refusing to eat for over two weeks. Doctors have alerted authorities to the inappropriate medical and living conditions in these facilities, and the difficulty in getting children into Australian hospitals. One doctor was fired after criticizing this system (Al Jazeera, 2019). More than 1,000 people were still detained in February 2019 in Nauru and other islands of Papua New Guinea.

Drawing by primary school aged child, Christmas Island (Australian HRC, 2014)

Child detention in Australia is heavily criticized by the international community and has degraded residents’ views of their own country. Daniel Webb, Director of Legal Advocacy at the Human Rights Law Centre said: “These children and their families have now been detained for over five years – imprisoned for fleeing the same atrocities our government comes here and condemns”. Alarming reports from the UN in 2016 stated that children in detention centres are often completely desperate and have “attempted suicide, self-immolation, acts of self-harm and depression”(CNN, 2018), even those living alongside their parents in the detention centres are implicated in this description. Children are affected by ‘resignation syndrome’, which means they lose the appetite to eat, to get out of bed, some of them refuse to speak, and worse. There are several cases of suicide attempts, even in children as young as 10 years old.

The Australian government has declared that Nauru’s detention centre will no longer be used in the border control system and that all children will leave the island. In February 2019, however, the campaign “Kids Off Nauru” revealed that children were nonetheless still detained on the island (World Vision, 2019). According to Al Jazeera, 109 of the children – supposedly all of them – have now left Nauru Island (Al Jazeera, 2019).

Detained children are being ‘swapped’ between Australia and the USA via a program set up under the Obama administration. Whether or not consent is obtained for these ‘resettlements’ in unknown (The Guardian, 2019).

Law on Child Detention

Children have an extensive corpus of rights powerfully enshrined throughout international and national human rights laws as well as in bodies of social, cultural and economic legislation. In particular, children have many specialised rights due to their status as minors. A central principle governing today’s conception of child rights is the child’s best interest: “In all actions concerning children, whether undertaken by public or private social welfare institutions, courts of law, administrative authorities or legislative bodies, the best interests of the child shall be a primary consideration.” (Article 3, CRC).

The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC): “The Convention on the Rights of the Child is the most widely and rapidly ratified international human rights treaty in history. Only the United States has not ratified the agreement” (End Children Detention, 2019). The major principle of the Convention, who’s 30th anniversary will take place in a few months’ time, is that children must be treated as children first and foremost. In accordance with the Convention, children have the right to access education, health care, as well as the right to grow up in an environment of happiness, love, and understanding. Children should also be informed about their own rights and participate in their realisation in an accessible and active manner.

Today in the case of immigration, child detention is always a child rights violation. “The detention of a child because of their or their parent’s migration status constitutes a child rights violation and always contravenes the principle of the best interests of the child [..],” (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2012).

Humanium denounces detention

Humanium exists to see the rights of children fulfilled; a raison d’être in opposition to the appalling violations child detention oversees. The detention of minors, for anything other than absolutely exceptional highly short-term circumstances in which detention is both in their own interests and in perfect accordance with prevailing law and standards, is unconditionally wrong. The deprivation of minors’ liberties and human rights as a result of their immigration status is something Humanium utterly condemns. We thus call for the unconditional and permanent abolition of child immigration detention.

Written by Adrian Lakrichi and Josie Thum

Further Reading

- Australian Human Rights Commission, ‘4 An overview of the children in detention’ (2014), Retrieved from: https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/4-overview-children-detention, accessed 24 July 2019.

- Global Detention Project, ‘Immigration Detention: “Never in the best interests of children”’ (2019), Retrieved from: https://www.globaldetentionproject.org/immigration-detention-never-best-interests-children, accessed 24 July 2019.

- Human Rights Watch, ‘We went to a US border detention centre for children and what we saw was awful’ (24 June 2019), Retrieved from: https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/06/24/we-went-us-border-detention-center-children-what-we-saw-was-awful, accessed on 24 July 2019.

- World Vision, ‘As last kids leave Nauru, World Vision calls on MPs to back new law for sick refugees detained offshore’(3 February 2019), Retrieved from: https://www.worldvision.com.au/media-centre/resource/as-last-kids-leave-nauru-world-vision-calls-on-mps-to-back-new-law-for-sick-refugees-detained-offshore, accessed 24 July 2019.

Bibliography

- ABC Action News, ‘Doctor compares conditions at immigration holding centres to ‘torture facilities’’ (24 June 2019), Retrieved from: https://www.abcactionnews.com/news/national/doctor-compares-conditions-for-children-at-immigrant-holding-centers-to-torture-facilities, accessed on 24 July 2019.

- ACLU, ‘Immigrant kids keep dying in CBP detention centres, and the DHS won’t take accountability’ (24 June 2019), Retrieved from: https://www.aclu.org/blog/immigrants-rights/immigrants-rights-and-detention/immigrant-kids-keep-dying-cbp-detention, accessed on 24 July 2019.

- Al Jazeera, ‘The fate of children who cross the US – Mexico border alone’, Podcast (7 June 2019), Retrieved from: https://www.aljazeera.com/podcasts/thetake/2019/06/fate-children-cross-mexico-border-190607151946636.html, accessed on 24 July 2019.

- Al Jazeera, ‘US relocates hundreds of migrant children from border facility’ (25 June 2019), Retrieved from: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/06/relocates-hundreds-migrant-children-border-facility-190625020427101.html, accessed on 24 July 2019.

- Al Jazeera, ‘Australia offshore refugees’ (14 Jun 2019), Retrived from: https://www.aljazeera.com/podcasts/thetake/2019/06/australia-offshore-refugees-190614151225050.html, accessed 25/07/2019

- Al Jazeera, ‘Australia set repeal medical care bill for offshore refugees’ (4 Jul 2019), Retrieved from: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/07/australia-set-repeal-medical-care-bill-offshore-refugees-190703080344628.html accessed on 24 July 2019.

- AP News, ‘US gov’t moves migrant kids after AP exposes bad treatment’ (25 June 2019), Retrieved from: https://apnews.com/a7a9acc4c6a546829a258e008d10d705?utm_source=Twitter&utm_campaign=SocialFlow&utm_medium=AP, accessed 24 July 2019.

- Atlantic, ‘Children were dirty, they were scared, and they were hungry’ (25 June 2019), Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/family/archive/2019/06/child-detention-centers-immigration-attorney-interview/592540/, accessed 24 July 2019.

- Australian Government, Department of Home Affairs, ‘Immigration Detention and Community Statistics Summary’ (31 January 2018), Retrieved from: https://www.homeaffairs.gov.au/research-and-stats/files/immigration-detention-statistics-31-january-2018.pdf, accessed 24 July 2019.

- Australian Human Rights Commission (HRC), ‘4 An overview of the children in detention’ (2019), Retrieved from: https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/4-overview-children-detention, accessed 24 July 2019.

- AZ Mirror, ‘Six inspectors visited six Southwest Key facilities. Here’s what they found’ (16 May 2019), Retrieved from: https://www.azmirror.com/2019/05/16/state-inspectors-visited-six-southwest-key-facilities-heres-what-they-found/, accessed on 24 July 2019.

- BBC News, ‘Nauru migrants: Last four children to leave island for US’ (3 February 2019), Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-australia-47107179, accessed 24 July 2019.

- BBC News, ‘Nauru refugees: The island where children have given up on life’ (1 september 2018), Retrieved from: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-45327058, accessed 24 July 2019.

- CNN World, ‘Children on Nauru in desperate need of help, activists tell Australia’ (20 August 2018), Retrieved from: https://edition-m.cnn.com/2018/08/20/australia/nauru-children-australia-intl/index.html, accessed 24 July 2019.

- End Children Detention, ‘The international human rights community affirms that immigration detention is a violation of the rights of children’ (2019), Retrieved from: https://endchilddetention.org/toolbox/issue-child-immigration-detention/international-law/child-rights/, accessed 24 July 2019.

- Global Detention Project, ‘Australia Immigration Detention’ (2019), Retrieved from: https://www.globaldetentionproject.org/countries/asia-pacific/australia, accessed 24 July 2019.

- Global Detention Project, ‘United States Profile’ (2019), Retrieved from: https://www.globaldetentionproject.org/countries/americas/united-states, accessed 24 July 2019.

- Global Detention Project, ‘Immigration Detention: “Never in the best interests of children”’ (2019), Retrieved from: https://www.globaldetentionproject.org/immigration-detention-never-best-interests-children, accessed 24 July 2019.

- Guardian, ‘Australia’s Loss is America’s Gain’: the Naru and Manus refugees starting anew in the US (29 January 2019), Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/jan/29/what-happened-to-the-deal-and-the-refugees-surviving-australian-and-us-politics, accessed 28 July 2019.

- Guardian, ‘It’s great to get kids off Nauru, but detention centres in Australia are like prisons’ (31 Octobre 2018), Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/nov/01/i-have-visited-detention-centres-in-australia-they-are-not-much-better-than-nauru, accessed 24 July 2019.

- Guardian, ‘This is an emergency: the volunteers bailing out migrants from detention’ (21 July 2019), Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/jul/20/us-migrants-bail-volunteers-emergency-immigration, accessed on 24 July 2019.

- GQ, ‘Trump’s child detention camps cost $775 per person every day’ (25 June 2019), Retrieved from: https://www.gq.com/story/trump-detention-camps-cost, accessed 24 July 2019.

- Human Rights Watch, ‘How to Help Children Detained at the US Border’ (26 June 2019), Retrieved from: https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/06/26/how-help-children-detained-us-border, accessed on 24 July 2019.

- Human Rights Watch, ‘We went to a US border detention centre for children and what we saw was awful’ (24 June 2019), Retrieved from:https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/06/24/we-went-us-border-detention-center-children-what-we-saw-was-awful, accessed on 24 July 2019.

- Marketplace, ‘The facilities that are housing children separated from their parents’ (20 June 2018), Retrieved from: https://www.marketplace.org/2018/06/20/southwest-key-nonprofit-detention-center/, accessed 24 July 2019.

- New York Times, ‘He’s built an empire, with detained migrant children as the bricks’ (2 December 2018), Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/02/us/southwest-key-migrant-children.html, accessed 24 July 2019.

- NBC News, ‘24 migrants have died in ICE custody during the Trump administration’ (9 June 2019), Retrieved from: https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/immigration/24-immigrants-have-died-ice-custody-during-trump-administration-n1015291, accessed on 24 July 2019.

- Pacific Standard, ‘Can we be sure only six migrant children have recently died in government custody?’ (23 May 2019), Retrieved from: https://psmag.com/news/can-we-be-sure-only-six-migrant-children-have-recently-died-in-government-custody, accessed on 24 July 2019.

- Rolling Stone, ‘Children inside texas detention centres describe squalid conditions’ (27 June 2019), Retrieved from: https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/texas-border-children-parent-separation-migrant-detention-centers-853055/, accessed on 24 July 2019.

- UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC), ‘Committee on the Rights of the Child, Report of the 2012 Day of General Discussion on the Rights of All Children in the Context of International Migration’ (28 September 2012), Retrieved from: https://www.refworld.org/docid/51efb6fa4.html, accessed 24 July 2019.

- World Vision, ‘As last kids leave Nauru, World Vision calls on MPs to back new law for sick refugees detained offshore’ (3 February 2019), Retrieved from: https://www.worldvision.com.au/media-centre/resource/as-last-kids-leave-nauru-world-vision-calls-on-mps-to-back-new-law-for-sick-refugees-detained-offshore, accessed 24 July 2019.