Realizing Children’s Rights in Chile

Despite Chile being among the more developed countries in South America, relatively shielded from political havoc, children face several hurdles that directly prevent them from realizing a life where all their rights are respected and upheld. Among the issues that persist in the lives of children in Chile, some include child labour, child trafficking and child poverty.

Children’s Rights Index: 9,22 / 10

Green level: Good situation

Population: 19.21 million

Pop. ages 0-14: 19%

Life expectancy: 80.33 years

Under-5 mortality rate: 7‰

Chile at a glance

Chile is a spatially low and narrow country, located along the western seaboard of South America. With its capital being Santiago, the country shares borders with Argentina to the east, while to its west lies the Pacific Ocean and on the north lies Peru and Bolivia.

The Andes mountain range dominates a significant part of the country’s landscape and the country’s extreme length results in diverse climate realities ranging from coastal deserts in the north to a colder sub-Antarctic southern region. Chile also experiences several catastrophic extreme natural events such as volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, tsunamis, fierce winter storms as well as severe summer droughts (Carmagnani, 2022).

A historical past characterized by Spanish colonization led to a cultural reality that heavily drew from Spanish culture and thus the population is largely mestizo (a blend of Spanish as well as Indigenous bloodlines). Regarding economic prosperity, like most of its Latin American counterparts, Chile did not depend as heavily on agriculture and mining but instead focused on developing an economy that relied on manufacturing as well which led to the country becoming one of the most urbanized countries with a burgeoning middle class.

Looking at the political climate, except for a military junta maintaining control and power over the country between September 1973 and March 1990, the country has been relatively free of coups and constitutional suspensions which are a rather common occurrence in the political history of its neighbouring countries (Carmagnani, 2022). However, it is important to recognize the seventeen-year strong coup under General Augusto Pinochet, as it was one of the bloodiest in 20th-century Latin American history and his dictatorship led to more than 3000 people dead and missing (BBC, 2020).

The president of Chile in 2022 is Gabriel Boric who is consequently the youngest president in the country’s history. His win came against a backdrop of months of unrest in 2019 that came as a result of inadequate social welfare, corruption and inequality. Several representatives began drafting a new constitution to replace General Augusto Pinochet’s 1980 charter and the new constitution was put to a referendum earlier in 2022 (Bartlett, 2022).

However, voters overwhelmingly rejected the new constitution with almost 62% voting against the progressive drafts reflecting a result that was not anticipated with margins of defeat being much larger than opinion polls had suggested. However, Boric stated he would work with the Congress and civil society to come up with a “new constitutional process.” (Buschschlüter, 2022)

Status of children’s rights [1]

The years between 1990 and 2006 saw milestone developments in regard to the realization of children’s rights. The elected centre-left coalition, the Concertación, implemented important policies after 1990 with the three consecutive governments of the coalition (Aylwin 1990–94, Frei 1994–2000 and Lagos 2000–06) making significant decisions concerning children’s rights. The Aylwin administration was strongly committed to the ratification of international treaties that had not been realized as a result of military dictatorship. On the 13th of August 1990, Chile ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) (Fuentes, 2010).

In 1992, the Ministry of Planning developed a National Action Plan in Favour of Children following the commitment of the president at the World Summit for Children in 1990 with the plan being considered the first effort by the Chilean government to promote coherent and coordinated policies in regard to issues of children’s rights.

The Frei administration (1994–2000) continued the strategy of the previous government by approving legal initiatives, which included a law protecting children from all forms of discrimination, an adoption law that ended discrimination against children born out of wedlock, a law against domestic violence, the regulation of national and international kidnapping, and the regulation of the duties and rights of parents concerning financial benefits obtained by the couple. In 1995, the government established the National Committee Against Child Abuse and, in 1996, launched the National Advisory Committee for the Prevention and Eradication of Child Labour (Fuentes, 2010).

In regard to specific treaties the country ratified, Chile specifically ratified the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict on the 31 July 2003, the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the sale of children , child prostitution and child pornography on the 6 February 2003, and the convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities on the 29 July 2008.

Addressing the needs of children

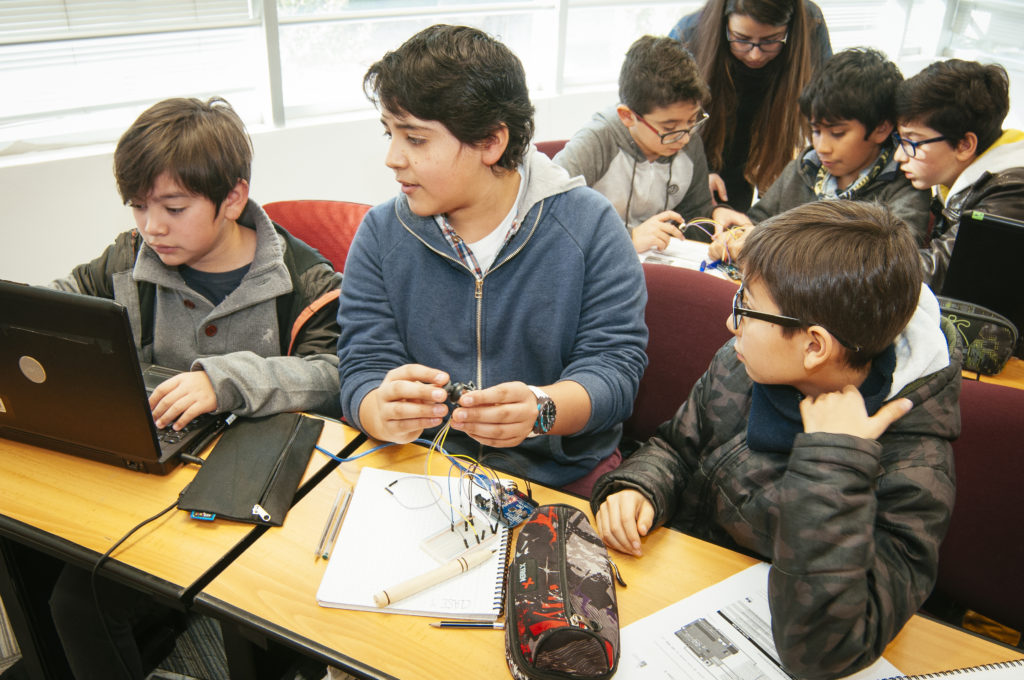

Right to education

In Chile, for children between the ages of seven and sixteen, education is mandatory for all children but while this is a statistic, the reality is that an estimated 75,000 children do not attend school and oftentimes are forced to abandon school in order to work and provide for their families. Additionally, glaring inequalities present themselves with regard to access to education as in the higher education system, the enrolment costs are among the highest in the world (Marlys, 2020).

The Covid-19 pandemic had massive repercussions on the education system globally and, while many moved to an online space to acquire education, the digital divide in Chile resulted in only 27% of the households in the low-income strata of the population having access to education online. A lack of devices where an obvious deterrent to gaining education and a lack of the internet as well as a lack of access to school lunches resulted in students not having the desire to connect (Human Rights Watch, 2022).

Furthermore, after schools returned to in-person classes, there were several cases of sexual harassment complaints, and sexist and violent behaviour, leading to student strikes and consequently a series of school closures across Chile’s capital. According to the government’s education department, schoolchildren’s sexual harassment complaints have increased by 56% in 2022 compared to the same period in 2018 (McGowan, 2022).

Right to health

For over twenty-five years, the National Health System (NHS) has been instrumental in providing centrally planned and cost-effective health services. However, with the government moving toward privatization, the NHS did not fit with the drive and this led to several repercussions affecting poorer sections of the population. A national health fund (FONASA) was created in 1981, which became the major source of state financing.

As social security was privatized, individuals paid FONASA directly, at a rate of 9 percent of their salaries. The only alternative was to rely on private health insurance provided by the Institutes of Health Security (ISAPRES). ISAPRES was launched in mid-1981 to finance private health services by establishing independent contracts with individuals or entities. ISAPRES could screen prospective clients by age, family size or health ‘risk’ and had the right not to renew yearly policies on expiration.

This led to the poorer sections not being able to afford ISAPRES and being able to only report to FONASA. Public hospitals steadily deteriorated, while the more affluent ISARES allied with major financial groups built their own ultramodern hospitals, and were only accessible to a small but wealthy section of the population. This led to a two-track system emerging where physicians and other health professionals increasingly opted for private practice, providing token services, or none at all, to public hospitals. This led to health becoming more of a commodity than a right (Sepúlveda, 1994).

Right to clean water and sanitation

Although the country was known to be one that had ample reserves of water, Chile has been struck for the past decade by a horrible drought with rain levels dropping by 20 to 40 percent and according to the World Resources Institute, Chile belongs to the list of countries that will be facing high water stress by 2040. About 1.4 million Chileans (8% of the population ) do not have access to drinking water or sewage and rural communities are hit the hardest as they are pitted against large companies seeking access to water (Langrand, n.d.).

Glaciers are responsible for providing Chile with much of its water but they are in danger of disappearing as rates of precipitation decline and extensive mining of the copper deposits beneath many glacial areas continues. It is estimated that if Chile does not take the required measures to preserve its glaciers, by the end of the century, half of the total ice volume would have melted thus depriving the country of its major source of freshwater (Roark, 2020).

Natural disasters have been a recurring phenomenon in Chile for the past two decades, such as the case of 2017, when surging floods in Santiago left millions without access to clean drinking water. Many attribute the country’s heightened susceptibility to floods to the rapid expansion of urban development and the loss of green spaces within the country, which has led to water having nowhere to go during storms (Roark, 2020).

Risk factors → Country-specific challenges

Child trafficking

Chilean women and children are the most common victims who are exploited in sex trafficking within the country, as are women and girls from Asia and other Latin American countries, particularly Colombia. Migrants’ vulnerability and inability to steer away from trafficking increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, with more than 30 percent experiencing job loss with limited to no alternatives amid regional movement restrictions.

Stricter immigration laws also contributed to heightened vulnerability in migrant populations, especially Venezuelans. Children staying in child protection centres are at further risk of potential abuse, including trafficking. Furthermore, Chilean authorities identified a significant number of children involved in illicit activities, including drug trafficking and theft and some of these children may have become trafficking victims. Traffickers subject Chilean men to labour trafficking in Peru and Chilean women to sex trafficking in Argentina, as well as other countries (U.S Department of State, 2021).

Child labour

In 2020, Chile made specific advancements that directly sought to eliminate the worst forms of child labour. The government published Law 21.271, which amended the Labour Code to require that a new list of hazardous activities and occupations for children and adolescents be published by the government, and ratified the International Labour Organization’s 2014 Forced Labour Protocol. The government additionally established the Tacna-Arica Bi-regional Roundtable to coordinate efforts between the Governments of Chile and Peru to prevent and eradicate child labour within the borders (Bureau of International Labor Affairs, 2021).

However, despite these attempts, children in Chile are subjected to the worst forms of child labour, including commercial sexual exploitation, sometimes as a result of human trafficking. Children are also subjected to involvement in the production and trafficking of drugs (Bureau of International Labor Affairs, 2021).

Furthermore, school dropouts have a direct correlation with child labour and children between the ages of five and seventeen often participate in labour activities. There are also major gender discrepancies within child labour with 9.5% of boys and 3.9% of girls engaging in the workforce.

The most common industries of work include restaurants, hotels, commerce, social services, agriculture and construction. Moreover, conditions have deep negative repercussions and approximately 70.6% of working children work at jobs that are deemed dangerous. A lack of public data and information is a direct demonstration of the county’s reality in addressing child labour (Marlys, 2020).

Child poverty

Between 2017 and 2020, rates of children and adolescents living in poverty rose from 13.9% to 15.6% with an estimated 703,045 children and adolescents living in income poverty.

In regard to extreme poverty, there was an increase of 2%, with more than 260,000 children and adolescents living in these conditions (Unicef, 2021). Furthermore, native and migrant children are two marginalized groups that are especially susceptible to child poverty in Chile as children from these communities do not have the same access to education and healthy lifestyles as other children, due to their family’s lower economic status and discrimination. In the country, they are often viewed as inferior due to their indigenous status (Marlys, 2020).

Children with disabilities

There is no specific program which addresses children with disabilities, making this an issue in Chile. Chile’s government began collecting data through a national survey on disabilities and dependencies, focusing on their prevalence in the country. The state would be financing teams to provide educational support for persons with disabilities.

Chile’s specialised protection system allowed for specific specialised facilities for children with severe disabilities, while other programmes were available for children with non-severe disabilities. More than 700 children with disabilities were participating in such programmes (OHCHR, 2022).

Environmental issues

Chile is highly exposed and vulnerable to multiple hazards such as earthquakes, volcanic activity and tsunamis coupled with issues that can worsen with climate change such as wildfires, floods, landslides and droughts. The country is experiencing an increase in forest fires. In 2017, forest fires impacted approximately more than 1,000,000 acres of vegetation, reaching record proportions. The area between Santiago and Puerto Montt is additionally more exposed to fire with an average of 3,000 to 5,000 fires each fire season (Climate Change Knowledge Portal, n.d.).

Written by Aditi Partha

Last updated on 19 December 2022

Bibliography:

Bartlett, J. (2022, March 11). Gabriel Boric, 36, sworn in as president to herald new era for Chile. Retrieved from The Guardian at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/mar/11/gabriel-boric-chile-president-new-era , accessed on 18 December 2022.

BBC. (2020, October 26). Chile country profile. Retrieved from BBC at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-19357497 , accessed on 18 December 2022.

Bureau of International Labor Affairs (2021). Findings on the worst forms of child labor-Chile. Retrieved from U.S Department of Labor at https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/resources/reports/child-labor/chile , accessed on 18 December 2022.

Buschschlüter, V. (2022, September 5). Chile constitution: voters overwhelmingly reject radical change. Retrieved from BBC at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-62792025 , accessed on 18 December 2022.

Carmagnani, M. A. (2022, December 13). Republic of Chile. Retrieved from Britannica at https://www.britannica.com/place/Chile , accessed on 18 December 2022.

Climate Change Knowledge Portal . (n.d.). Country Profile- Chile. Retrieved from Climate Change Knowledge Portal at https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/chile/vulnerability , accessed on 18 December 2022.

Fuentes, C. (2010). Protecting the Child in Chile: Civil Society and the State. In C. Fuentes, Citizen Action and National Policy Reform: Making Change Happen (pp. 109-111). https://www.gov.uk/research-for-development-outputs/protecting-the-child-in-chile-civil-society-and-the-state#links , accessed on 18 December 2022.

Human Rights Watch. (2022, April 25). Submission to the Committee on the Rights of the Child Review of Chile. Retrieved from Human Rights Watch at https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/04/25/submission-committee-rights-child-review-chile , accessed on 18 December 2022.

Langrand, M. (n.d.). Part 1: Chile’s battle to reclaim its water. Retrieved from Geneva Solutions at https://genevasolutions.news/explorations/the-water-we-share/chile-s-battle-to-reclaim-its-water , accessed on 18 December 2022.

Marlys, M. (2020, November 5). The fight against child poverty in Chile. Retrieved from Borgen Project at https://borgenproject.org/child-poverty-in-chile/ , accessed on 18 December 2022.

McGowan, C. (2022, March 27). Students force closure of Santiago schools over sexual harassment and violence. Retrieved from The Guardian at https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2022/mar/27/chile-students-close-schools-protest-sexual-harassment-violence , accessed on 18 December 2022.

OHCHR. (2022, May 25). Experts of the Committee on the Rights of the Child commend Chile for its “My Lawyer” programme for children, ask about violent responses to child protests and the situation of children with disabilities. Retrieved from OHCHR at https://www.ohchr.org/en/news/2022/05/experts-committee-rights-child-commend-chile-its-my-lawyer-programme-children-ask , accessed on 18 December 2022.

Roark, J. (2020, March 17). 10 Facts about sanitation in Chile. Retrieved from Borgen Project at https://borgenproject.org/10-facts-about-sanitation-in-chile/ , accessed on 18 December 2022.

Sepúlveda, C. (n.d.). The Right to Child Health: The development of primary health services in Chile and Thailand. Florence: Unicef., pp.1-71, https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/131-the-right-to-child-health-the-development-of-primary-health-services-in-chile-and.html, accessed on 18 December 2022.

Unicef. (2021). Country Office Annual Report 2021. Unicef, https://www.unicef.org/reports/country-regional-divisional-annual-reports-2021/Chile accessed on 18 December 2022.

U.S Department of State. (2021). 2021 Trafficking in persons report: Chile. Retrieved from U.S. Department of State at https://www.state.gov/reports/2021-trafficking-in-persons-report/chile/ , accessed on 18 December 2022.

[1] This article by no means purports to give a full or representative account of children’s rights in Chile; indeed, one of many challenges is the scant updated information on the children in Chile, much of which is unreliable, not representative, outdated or simply non-existent.