Realizing children’s rights in Antigua and Barbuda

Antigua and Barbuda has a special status: it is part of a group of seven states placed under UN supervision via the UN Barbados and the Eastern Caribbean Multi-Country Office. The last report by the Committee on the Rights of the Child in the country is encouraging, but much remains to be done for children’s rights to be fully respected. The country will have to report to the Committee on its progress, and it will be interesting to read both the report and the Committee’s response.

Children’s Rights Index: 8,05 / 10

Yellow level: Satisfactory situation

Population: 97,928

Pop. ages 0-14: 21.8%

Life expectancy: 77 ans

Under-5 mortality rate: 5.4‰

Antigua and Barbuda at a glance

Tourism, the leading economic sector of this ‘Land of 365 beaches’, contributes to 80% of its GDP and is an important source of employment (World Bank Group, n.d.). Already weakened by Hurricane Irma in 2017, the economy and the population, particularly the most vulnerable people, were further impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic (Moore, 2020, p. 6). The OECD considers Antigua and Barbuda a tax haven – a status the government(a parliamentary system) is endeavouring to change through greater transparency of banking and tax institutions (Observatoire des Amériques— Montréal).

Status of children’s rights [1]

On an international level, Antigua and Barbuda has been part of the Convention on the Rights of the Child since 1993. In 2003, it ratified the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, concerning the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography. However, although it has signed this protocol, it has not submitted any reports – the first one was due on 30 May 2004.

Antigua and Barbuda could also make more efforts in terms of ratifications. The Optional Protocol on the Convention onthe Rights of the Child on a communications procedure, the Optional Protocol to the Convention of the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict as well as tools linked to fundamental human rights, such as the International Pact on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Social, Economic and Cultural Rights still await ratification.

Neither is the country a party to the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance or to The Hague Conventions on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction and on the Protection of Children and Co-operation in Respect of Intercountry Adoption.

In 2016, however, it did ratify the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, and adopted other institutional and political measures linked to the rights of the child, as highlighted by the Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC)(Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017). In 2015, in a sign of goodwill, the country passed laws that would help usher in reforms regarding children’s rights [2].

These laws have allowed the best interest principle to be inscribed in the legislative system (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017, p. 5). As for the guiding principle of young people’s participation, it is not recognised by law, but efforts are being made to put it into practice, through various mechanisms in schools.(Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017, p. 5).

A recurrent problem for the state is the severe lack of data. As the 2017 final observations of the CRC explicitly point out, this makes it difficult to plan, implement and evaluate public policies to protect children’s various rights. This may be partly explained by budget cuts in the education and health sectors and other funding and resource allocation problems that would ensure the rights in the International Convention on the Rights of the Child are enforced, especially for the most vulnerable (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017, p. 2).

However, the CRC states in its 2003 General comment no. 5 on the Convention’s general measures of implementation that data is essential for the application of the rights in the Convention (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2003). For example, there is no reliable data, no national policy for disabled children and no legal definition. It is, therefore, impossible to know the situation of this group of children or to develop adapted services that would allow their rights to be respected. Moreover, no independent mechanism tasked with monitoring children’s rights exists (Committee on the rights of the child, 2017, p. 3).

Addressing children’s needs

Right to education

Education is compulsory for all children between the ages of five and 16, and primary and secondary education is free (Antigua and Barbuda: Children’s rights references in the universal periodic review, 2016). At the same time, the scarcity of educational establishments, and a lack of pedagogical tools make the right to education difficult to apply (Committee on the rights of the child, 2017, p. 11). Moreover, the Convention is not included in school programmes, preventing children from being exposed to it, knowing their rights and asking that they be respected.

Right to protection

The right to protection concerns the physical and mental well-being of minors. However, corporal punishment is commonplace in Antigua and Barbuda. The 1949 Corporal Punishment Act and the 1956 Prison Act permit the use of flogging in case of failure to respect carceral discipline (Committee against Torture, 2017, p. 8).

Violence is deeply entrenched in customs – it is legal to inflict corporal punishment not only at home but in all establishments linked to child development, including in the education system (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017, p. 8) and prisons (Committee against Torture, 2017, p. 8). For example, according to a 2008 law still in force, the principal and the deputy principal of a school have the right to administer corporal punishment, even though the 2015 Child Justice Act forbids such punishment to be administered to a child.

With the 2015 Children (Care and Adoption) Act, the country is able to address the issue of child abuse, although more effort is still required to document and stop abuse towards minors. The country contains few help centres for victims and has no mechanism to register and monitor complaints (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017, p. 6).

Right to health

In Antigua and Barbuda, all children below the age of 16 are entitled to free medical care, and vaccination coverage is good. Protecting and improving young people’s mental health is also a concern for the state.

However, in its 2017 report, the CRC observed a large increase in obesity and malnutrition among minors and a dearth of qualified child psychiatrists and community mental health services (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017, p. 9). Moreover, with no law banning their sale and consumption, the consumption of alcohol and marijuana is increasing among young people (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017, p. 9).

Regarding the sexual health of minors, the Planned Parenthood Association provides contraceptives and free advice services. However, sexual and reproductive health is not taught at school, and children receive little advice or attention when confronted with problems of development, mental health and reproduction (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017, p.9). This results in a high number of early pregnancies, which can have a negative effect on girls’ education (UNESCO, 2017).

Problems of coordination between the different organisations working in this field leave little hope for a viable strategic policy to prevent these pregnancies (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017, p.9). Nonetheless, efforts are being made for people living with HIV. In line with preventative efforts, the risk of transmission from pregnant mother to child has been practically eliminated(Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017, p. 10). However, more and more girls are being infected with HIV, and the accompanying stigmatisation and discrimination hinder access to care for people living with HIV (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017, p. 11).

Risk factors → Country-specific challenges

Child trafficking

People and children trafficking is a major issue plaguing the country (2019 Trafficking in Persons Report: Antigua and Barbuda, n.d.). Laws, such as the 2010 law on the prevention of human trafficking, are being modified and other measures are being put in place to address the issue. A National Action Plan on the prevention of human trafficking was even implemented between 2016 and 2018. However, data is sparse on this subject; a shortage of resources makes it difficult to identify victims; and care, aid and accommodation services are lacking to help victims of trafficking (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017, p. 12).

Nonetheless, Antigua and Barbuda has made efforts, notably in 2015 with an amendment to the 2010 Trafficking in Persons (Prevention) Act, and with the creation of a Sex Offence Unit within the police force in 2008 (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017, p. 7) tasked to fight sexual exploitation, which can be an aim of child trafficking.

Child labour

Generally, it is illegal to employ children under 14 years of age. Minors aged between 14 and 18 may be employed outside school hours, and a medical authorisation is necessary for night work. However, when it comes to dangerous work, the law is very vague concerning the protection of minors (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017, pp. 11–12).

Discrimination

Discrimination is frequent in Antigua and Barbuda, but little data is available for effective and efficient political action, particularly when it comes to foreigners (Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, 2007). As a result, efforts are being made to better integrate expatriates: children from an immigrant background can attend state school as soon as they arrive, and no longer have to wait for the two years previously required. However, due to a lack of resources in the education system, these children still do not go to school, and no mechanism exists to remedy this situation (Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, 2007, p. 4).

Disabled children

Similarly, disabled children face real challenges in Antigua and Barbuda. There is no law or policy to support them, and there is a real lack of inclusion for these children with specific needs, notably in terms of basic services. Moreover, ease of access for disabled people is not a legal requirement.

Services to monitor the development of these children and to include them as much as possible in society are lacking (Committee on the rights of the child, 2017, p. 8). This problem of accessibility also affects certain groups of children, particularly those that are vulnerable, such as children living in poverty, migrant children and informally adopted children (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017, p. 4).

Child justice

Child justice is determined by an eponymous act passed in 2015 and implemented in 2016. Despite this recent law, which is supposed to follow the guiding principles and rights contained in the Convention, there are many areas for improvement. For example, the minimum age of criminal responsibility is very low: eight-year-old children can be arrested and taken to court. Few ways to protect young people exist, and there are notably few possible substitutions for legal procedures, with probation the only alternative to sentencing and imprisonment (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017, p. 13).

When they are not placed with adult prisoners (Committee against Torture, 2017, p. 7), children referred to residential centres are held in the Boys’ Training School, a programme which respects neither the Convention on the Rights of the Child nor the United Nations Rules for the Protection of Minors Deprived of their Liberty (Havana Rules) (Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2017, p. 13).

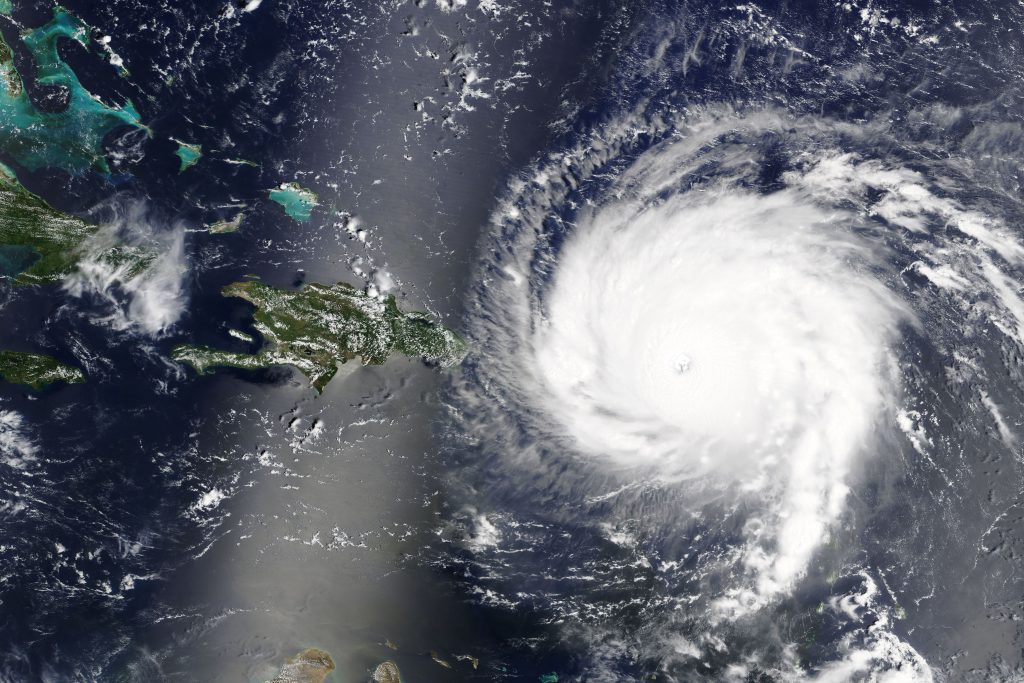

Environmental challenges

Due to its island status and its position in the Caribbean, Antigua and Barbuda is on the frontline with respect to the impacts of climate change, including a rise in sea levels and an increase in the likelihood of extreme weather events (World Bank Group, n.d.) – regular hurricanes and storms are already a common occurrence (CIA, 2022), as Hurricane Irma demonstrated in 2017 (Moore, 2020, p. 6). The sexual violence to which girls can be subjected in overcrowded shelters is one example of the impact such environmental events have on the respect for children’s rights. (Crisis update: restoring dignity and livelihoods after storms in the Caribbean.)

Moreover, because of its topography, Antigua and Barbuda is regularly subject to droughts (Momsen, n.d.). The country is also vulnerable to weather events in the region; the eruption of the volcano La Soufrière in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines caused a humanitarian and economic crisis that also seriously affected Antigua and Barbuda (Agence France Presse, 2021).

Written by Juliette Bail

Translated by Alex Macpherson

Revised by Jean-Christophe Brunet

Last updated on February 26, 2022

References:

2019 Trafficking in Persons Report: Antigua and Barbuda. (n.d.). Consulté le 15 février 2022, du site internet U.S Department of state: https://www.state.gov/reports/2019-trafficking-in-persons-report-2/antigua-and-barbuda/

Agence France Presse. (2021, 14 avril). Longue crise en perspective, prévient l’ONU. Consulté le 24 février 2022, du site internet La Presse: https://www.lapresse.ca/international/caraibes/2021-04-14/saint-vincent/longue-crise-en-perspective-previent-l-onu.php

Antigua and Barbuda: Children’s rights references in the universal periodic review. (2016, 9mai). Consulté le 17 février 2022, du site internet Child Rights International Network: https://archive.crin.org/en/library/publications/antigua-and-barbuda-childrens-rights-references-universal-periodic-review.html

CIA. (2022, 16 février). Antigua and Barbuda. Consulté le 25 février 2022, du site internet The World Factbook: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/antigua-and-barbuda/

Comité contre la torture. (2017, 30 août). Observations finales concernant Antigua-et-Barbuda en l’absence de rapport.Consulté le 15 février 2022, du site internet des Nations Unies: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G17/253/86/PDF/G1725386.pdf?OpenElement

Comité des droits de l’enfant. (2003, 27 novembre). Observation générale °5. Consulté le 24 février 2022, du site internet des Nations Unies: https://www.right-to-education.org/sites/right-to-education.org/files/resource-attachments/CRC_Observation%20_Generale_5_2003_FR.pdf

Comité des droits de l’enfant. (2017, 30 juin). Observations finales concernant le rapportd’Antigua-et-Barbuda valant deuxième à quatrième rapports périodiques.Consulté le 15 février 2022, du site internet des Nationes Unies: https://docstore.ohchr.org/SelfServices/FilesHandler.ashx?enc=6QkG1d%2fPPRiCAqhKb7yhssgYL1OdqFkpqxKws0oHsu%2fSCfv%2fZans%2fSEyT%2b0yyvbiHMTXKzZT0KDiD15SZF0YdQT9cUcBCu51xr%2bWUUdpBmAMpayUqs4XtjLFhmkHOcKO

Comité pour l’élimination de la discrimination raciale. (2007, 11 avril). Examen des rapports présentés par les États parties conformément à l’article 9 de la Convention. Consulté le 25 février2022, du site internet des Nations Unies: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G07/417/04/PDF/G0741704.pdf?OpenElement

Dernières informations à propos de la crise : Récupérer la dignité et rétablir les moyens de subsistance après la crise aux Caraïbes. (2018, 15 août). Consulté le25 février 2022, du site internet ONU Femmes: https://www.unwomen.org/fr/news/stories/2018/8/feature-caribbean-humanitarian-update

Momsen, J. D. (n.d.). Antigua and Barbuda. Consulté le 24 février 2022, du site internet Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/place/Antigua-and-Barbuda

Moore, W. (2020, juillet). Antigua and Barbuda : Covid-19 Heat report human and economic assessment of impact.Consulté le 25 février 2022, du site internet UN Women: https://caribbean.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Field%20Office%20Caribbean/Attachments/Publications/2020/Human%20Impact%20and%20Economic%20Assessment%20of%20Impact%20%20Antigua%20%20Barbuda.pdf

Observatoire des amériques – Montréal. (n.d.). Antigua et Barbuda.Consulté le 13 février2022, du site internent de l’UQAM: https://www.ameriques.uqam.ca/spip.php?article144&lang=fr

UNESCO. (2017). Grossesses précoces et non désirées: recommandations à l’usage du secteur de l’éducation.Consulté le 29 mars 2022, du site internet UNESDOC: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000248418_fre

World bank group. (n.d.). Antigua and Barbuda. Consulté le 15 février 2022, du site internet Climate Change Knowledge Portal: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/antigua-and-barbuda

[1] This article in no way claims to give a complete or representative account of children’s rights in Antigua and Barbuda: one of the many challenges here is the lack of up-to-date information on children, particularly translated into French or English. This article is based mostly on sources issued by the United Nations, which warrant the corroboration of resources from other organisations.

[2] For example, law no. 23 of 2015, relating to child justice, law no. 24 of 2015, relating to childhood (protection and adoption), and law no. 27 of 2015, relating to familial violence